This site contains student blog posts and teaching materials related to ENGL 89500: Knowledge Infrastructures, a seminar taught by Prof. Matthew Gold in Spring 2020 in the Ph.D. Program in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. We will leave the content of the site available as a record of our class and a resource for others who might be interested in the topics we covered. Please contact us if you have any questions about the material that appears on the site.

Midsummer share

This seemed relevant to class discussions so thought I’d share: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/toward-new-alexandria/

Opening: Kelty, Groom, Eve, and Zuckerman

Some Thoughts/Qs:

- Groom’s inspiring 2009 piece reminds me of Hannah Alpert-Abrams’ writing. Another DHer who left academia, Alpert-Abrams has since gone on to make all of her academic job-search/grant materials freely available online to help academic jobseekers. Groom now runs Reclaim Hosting (a paid but highly affordable hosting platform). On leaving academia and these resources: is there something about being in the field that makes free & open aid difficult/impossible/unideal (even at CUNY)? What do we make of the lingering prestige of costly and dense resources and content in this field? For me, Groom makes an excellent point about the way he communicates and the work he does….

- Zuckerman got me thinking into a politics of free tech/infrastructure as well as goals or ideals for its application(s). A few related ways into this might be:

- can a FLOSS revolution be fully achieved within/alongside existing institutional structures: academia or even Google/Microsoft? Knowledge infrastructures certainly don’t only originate in such places. More broadly, should we focus on removing existing structures of power—“the university as we know it” or “Google”—or on what Zuckerman calls “filling in the gaps”? I am interested in our take on the BBC/NPR dichotomy of comprehensive vs complementary change.

- A la Zuckerman’s question of not only how we fund public infrastructure, but what would it do: how might we go about getting past our “failures of imagination,” and consider infrastructure that work for the public (not simply academic research and corporations)? Can we make the public option “our work” or “humanities work”? How might/mightn’t this be doable?

- Zuckerman and Eve both reference UK models of state-sponsored media (among others), but what should the US government’s role be in all this? How do we understand the line between protecting citizens and censorship (esp. in an American context where censorship is a particularly hot topic)?

- Kelty’s proposal of reorienting power around “recursive publics” as a counter to various organizations is an interesting and important point. I wonder, though, how we bridge the gap of informed publics (those who might become recursive publics) and targeted communities for whom such concepts might seem indigestible. What is the likelihood that our “recursive publics” will again divide a bourgeois educated elite and the voiceless (how exactly are we to interpret those “geeks” to whom Kelty frequently refers)? Where and how would such work need to begin to promote inclusivity? How do we ensure that folks are not left out this power reorganization?

A Few Resources:

Many in my community have expressed anxiety over accessing materials for finishing up coursework or teaching. The significance of open and free resources becomes unmistakable in such moments. As this week is dedicated to openness, I thought I’d share a concise but curated list of a few open and free resources that connect to our course:

- Dan Shiffman (of NYU’s ITP program and the Processing Foundation) shared his Open Studio syllabus online which covers OA/FLOSS topics and his site The Coding Train provides free instructional coding tutorials (often on p5.js and Processing– two FLOSS tools for creative coding with many free examples). Another, more DH-y, resource you might explore is Programming Historian.

- Manifold’s UMN project site and the Debates in the Digital Humanities series house many excellent works.

- Various academic presses have open book pages, a couple select choices might be: NYU’s Open Square (home to Andre Brock’s new Distributed Blackness), and Duke UP.

- Humanities Commons’ CORE Deposits is home to ample OA works and their Academic Job Market Support Network allows users to read and share examples of job market materials—endeavoring to make not only research materials, but the entire field, accessible.

- Given that our lives are now more digital than ever, Tactical Tech’s Data Detox Kit shares accessible and flexible tips for improving personal internet privacy/security.

- And, of course, there is always the Internet Archive and their Open Library.

Troubling Post

At risk of perversity, I would like to use this week’s readings to discuss how our current moment presents a place of analysis regarding capitalist infrastructure and crisis (or perhaps its fabrication). Through the lenses of Harroway and Ahmed, the current social threats posed by the epidemic seem to draw from a place of “disorientation,” a state of queered perception of the body (social, politic, bio’logical’) in which the public is forced to abandon the standard perceptions of ourselves as discrete, sanitary units. By necessity, we contend with ourselves as an interconnected assortment of “critters” and must address new forms of assemblages and articulations that can accommodate the introduction of a new contagion into our “holobionts.” Such states of disoriented symbiosis extend beyond the molecular level to also be exhibited in the realms of the social and international, with common interactions and commercial engagement being forbidden and even the foundational unit of Western capital (if I remember Reich correctly) becoming itself a site of queered interaction. (Can the familial hug now become a risk of contagion? Does mortality and violence now emerge in those normative spheres that supposedly exempt such risks?)

Such disruptions of the social have a Latourian bent to them when we recall that this disruption of the social occurs simultaneously with disruptions of the infrastructure that produce the social and have permitted the introduction of this new “critter” into our present “Chthulucene.” If there is anything to (re)learn from COVID, it is the sheer interconnected nature of our global holobiont and the complete incapability between its self-awareness and continued functioning. The revealed precarity of the ‘gig economy’ and ‘right to work’ legislation has prompted suspensions of rent, loans, and investment – the very structural techniques that have facilitated the development of late-stage capitalism. Despite years of a rising economy we find our individual lives unsure of their continued value as productive workers and our ability to engage in necessary consumption patterns.

In essence, the discrete markers of growth and structural sufficiency (quantitative rise in NASDAQ/DOW/S&P indexes, low unemployment) are revealed insufficient when the underlying network becomes the target of focus. That economic markers are insufficient is a common critique and needs little discussion; what is curious is why these markers must be discrete. Why, given the recurring realities of the “Cthulucene” does capital return to the limitations of digital logic, presenting the crisis of one locale/person/community as exempt from the continual circulation of globalism?

Questions:

– Are crises of capital produced by direct ‘interruptions’ of the “Cthulucene” or by moments of awareness?

– Why does discretionary logic seem so crucial to capital when it must manage non-discretionary logic for it to expand (consider the likelihood that ‘distance learning’ may be expanded by some universities after the crisis or that more offices may ask workers to perform labor from home during ‘off hours’)?

– How does one permit a continual awareness of the “Cthulucene” instead of a flux between its forgetting and remembrance?

– Are there crises that can escape the expansion of capital (many have already made fortunes off the loss of gains from 2008)?

Intervention Thoughts

So I want to voice some thoughts on the planned intervention and consider explicit next steps for getting this off the ground. (Feel free to correct me if I’m off – my brain is off kilter this week for some strange reason….) Regarding data, I think we still need to figure exactly what data we are looking to collect in general (social media vs. instructions vs. individual ethnographies) and that may be a few more conversations until consensus is reached (e.g. determining group ethical positions on what data). Given that this conversation and the possible human subject questions that follow may take a tad more time than desirable, I believe that we should at the very least prioritize getting the project’s off the ground first and then reassess our data later. I believe this entails the following:

- Infrastructure. Let’s get the archive platform and submission system up and running so we can start collecting data when possible. I suggest using Omeka since it’s open-source and is better supported by the GC’s resources (I know this is Stefano’s platform for his work for instance).

- Participants. While it’s likely annoying to ask for participation while the specifics are still in the air, it may be helpful to start building up a sense of what data we have access to (e.g. only what our group can access vs. larger GC community vs. CUNY wide).

- Preliminary data. We’re already on this but might as well make it explicit: let’s try throwing together what data we can, even if it’s data we may reject later. For anyone that wants to add on to the web scraping but haven’t had much experience with API’S, the GC Digital Fellows made a rather straightforward guide for making a Twitter bot that we can use (I’ll add the link when I can find it). I also have an old RSS feed reader that we can tinker with if we want to probe new sources as well.

This is all I have off the top of my head. Any thoughts? Addendums?

Queen’s College Resources

A colleague shared resources Queens College is sharing with instructors during the outbreak. i’ve also uploaded a file to the Commons blog. http://englishonline.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/

CUNY Students via Twitter

After yesterday’s discussion, I decided to continue scanning Twitter for some of the more recent student reactions to CUNY’s treatment of the novel coronavirus outbreak in NYC. Simply enter “CUNY” into Twitter’s search query as I did, and behold as the results speak for themselves…

Continue readingResources discussed today

The University is NOT a Commons (Unless We Make It One)

I want to pick up from where we left off last week: is there any value in performing service work within an institution? I think this is a valid point of entry into the conversation about commoning because some forms of service – e.g., sitting on committees, mentoring colleagues, organizing events on campus, and advising students – have a great potential to catalyze a practice that David Harvey understands as “produc[ing] or establish[ing] a social relation with a common” (75), one that is both collective and non-commodified. Allow me to take a step back – Harvey frames “the right to the city,” the larger paradigm within which he engages with the urban commons, as far more than a right of access urban resources: “it is a right to change and reinvent the city more after our hearts’ desire” (4). My reason for arguing in favor of performing certain kinds of service – notwithstanding some legitimate concerns that have been raised in class and elsewhere – is that it is often one of the few avenues we (yes, graduate students, contingent faculty, and precarious workers especially) have to exert a similar right to shape the infrastructure of knowledge production/dissemination within which we operate.

While reworking an institution as inherently conservative as the university is, into a truly (and not only performative) radical haven is beyond our capacity, the value of commoning may lie beyond such grand goals. Whether we are taking an active interest in the clouding agreements in which the institution engages, serving on a student association, or attending tedious department meetings, I think there is value in engaging in service that goes beyond monetary retribution – it is, after all, of little surprise that we are disincentivized from coming together and to propose change from below. Rather, what we gain is being part of a dissonant conversation that makes the institution; attuning to like-minded voices within it; and contributing to it with otherwise modes of engagement. For example, following Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s lead, through “generous thinking” (expressed in the chapter we read for this week, through David Foster Wallace’s concept of “giving it away”) we are already performing and perpetuating “means of escaping the self-destructive spiral of addiction and self-absorption that constitutes not an anomalous state but rather the central mode of being in the contemporary US” (152).

I thus want us to think of commoning as an ethos, as ways of engagement through which we are already hacking and reshaping academic (and knowledge) infrastructures that are, very much like Harvey’s city, dominated by capitalist class interest. The university is NOT a commons, unless and until we make it one through collective political action. From this perspective, commoning is inevitably part of our work as scholars.

Looking forward to our class discussion and to proposing concrete examples of commoning spillages and outliers. In the meantime, below are some questions I’d like to invite you to think about. Stay safe, all!

- How do the models of commoning proposed by this week’s reading stand in relation to Stefano Harney’s and Fred Moten’s understanding of the Undercommons?

- Is commoning inherently good?

- Where do we stand, with knowledge infrastructures in mind, in relation to the Lockean formulation of the fair market (76)?

- What are some of the limitations of the commons of knowledge proposed by Fitzpatrick, Hess, and Ostrom?

SPARC, Sustainable Knowledge Infrastructures, and Emergent DH Praxis

Hi all,

I’m inclined to start things off by noting some of countervailing forces present in this week’s readings — one public-democratic, another private-capitalistic — each fighting for a foothold on the emergent knowledge infrastructures in the academy. In an attempt to frame our thinking on the topic, I abridged a series of associated themes, ethics, and practices from either set into a single-sentence bullet below:

- public-democratic: collaborative interventions aimed at facilitating more sustainable knowledge infrastructures among the academy and other social sectors, in turn channeling multivalent ways of knowing, DYI and hacker praxis, along with culturally situated acts of recovery and historical restoration.

- private-capitalistic: the neoliberal capitalization of higher education, by means of which free-market actors aggregate, analyze, and monetize academic knowledge production, effectively dispossessing scholarly and educational practices of their infrastructural sovereignty.

In what ways might we collaboratively leverage a DH-driven praxis to trouble or disrupt the data-driven exploitation of academic knowledge practices?

How might euro-centric academic knowledge production — specifically those aimed at archiving and representing indigenous data without consultation — fall into the equation? In what ways might Liu’s commentary on the hack/yack debacle inform your answer?

***

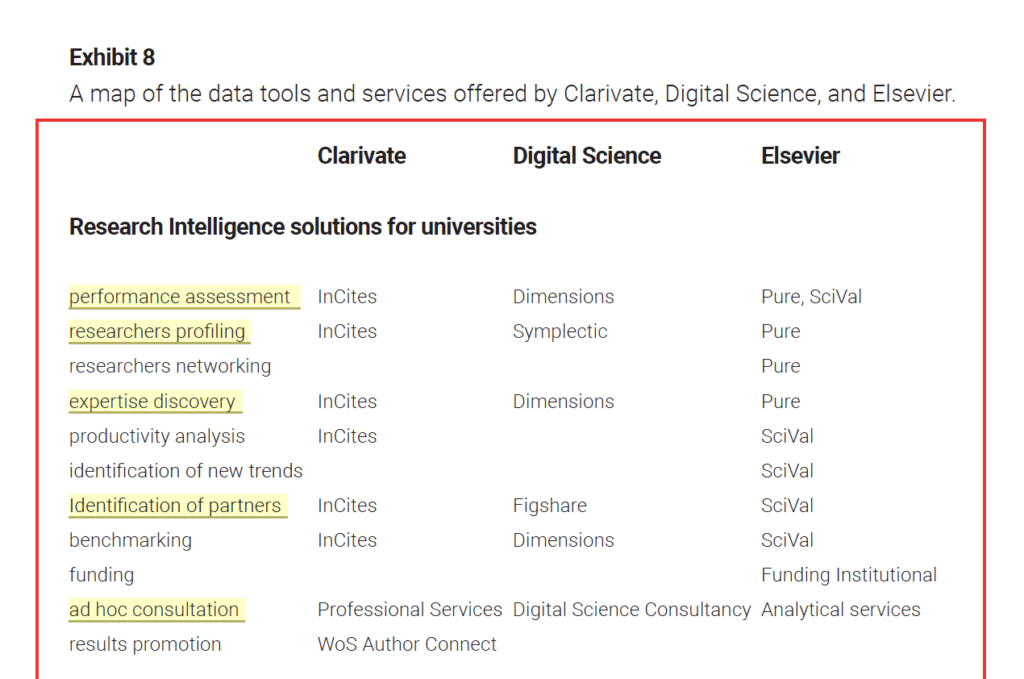

Moving forward, I feel it incumbent upon me to at least unpack some of the SPARC Landscape Analysis, if only because it is such a helpful document for working within the interventionist praxis of CI studies, not to mention critical university studies. Key to either project is the painstaking act of parsing infrastructural minutiae underlying individual company behavior, while further attending to how such nuances operationally play out across the wider neoliberal agenda of the academic publishing industry. For example, in the first half of Exhibit 8 below, the report chronicles “research intelligence solutions for universities” of Clarivate, Digital Science, and Elsevier, affording us a strong case for better understanding vested industry patterns — such as an inter-organizational view on which data-analytics services embody industry benchmarks.

I would at this point like to further reiterate some of the more pressing points of tension reported by SPARC in their analysis, such as their emphasis on accelerated rates of “commercial acquisition of critical infrastructure in [academic] institutions” (2). What’s more, notes SPARC, companies like Elsevier are well into the process of building and rolling out data analytics services intended to collect, parse, evaluate, and ultimately monetize data from the academic community, ranging from learner analytics and research output to productivity analysis and expertise discovery (31). Earmarking the same names over and over again — such as Cengage, Elsevier, and Pearson, whose 2018 annual revenues respectively totaled at $1.47, $2.54, $5.51 billion — SPARC urges higher-ed institutes to be wary of the educational services of these companies, which come with built-in data analytics that serve to profit from the capitalization of ongoing academic practices.

Which details or figures do you recall reading in the SPARC Landscape Analysis? Why did they stick out?

How might have the report been written differently to reach a wider audience, if at all?

Are there complementary ways in which we might synthesize these findings to reach not only the academic community, but also broader publics?

How might an awareness of such minutiae prepare us to challenge data analytics companies like Elsevier?

***

I apologize if this part of my blogpost comes off as at all rambling; much of it is my attempt to troubleshoot a few interesting but elusive comments from the prolegomena to “Sustainable Knowledge Infrastructures.” In it, Geoffrey C. Bowker compares a kitchen faucet to an accredited academic journal — which is funny, I agree, before turns out to be a tad complicated as far as the ontology/phenomenology of infrastructures are concerned. (More on that later.) More interesting, at least in retrospect, is his definition of infrastructure as not a what but a when — “The question is not so much “what is an infrastructure?” as “when is an infrastructure?” (204) — which is best understand via his claim that “to be infrastructural is to be in a subtending relationship with” (204). That is, according to Bowker, infrastructures come and go; they are contingent, nary but an indexical, named into being in terms of a complex network of interdependent utilities; or as Susan Leigh Star & Karen Ruhleder assert, “infrastructures are always relational: one person’s infrastructure is another ‘s site.”

Let’s go back to the kitchen faucet and the credentialed journal — could it be intended as a template to understand infrastructures across infrastructures, both of the physical and the knowledge variety? …

“It is clear that the taken-for-granted nature of turning on a tap and expecting water to come out of the faucet is equivalent to turning to an accredited journal and expecting knowledge to come out.”

Bowker (203)

Might Bowker’s “formal equivalence” in this case concern only the subject, the infrastructure (of the faucet), or perhaps even a synthesis of both?

How in particular does this formulation factor into the broader context of his argument for sustainable knowledge infrastructures? Why or why not?

For both the water/knowledge supply network, unseen backchannels surely abound. But I suspect the value in recognizing that — while we can always pipes can be seen knowledge infrastructures are consonant with physical is coming to terms with with phenomenological impression of either activity. As Susan Leigh Star & Karen Ruhleder write, “infrastructures are always relational: one person’s infrastructure is another ‘s site.”